Our attorneys have been assisting the Orange County and Southern California communities for over 40 years.

By: John A. Montevideo and Michael K. Teiman

Workplace injuries are all too common in California. While on the decline since 1999, 2018 and 2019 saw a rise in fatal workplace injuries to well over one fatality a day (422 fatalities in 2018 and 451 in 2019). Many of these fatalities occur around some type of product or heavy machinery. Indeed, in 2019 over 12% were by contact with an “object or equipment”; something that has remained at that rate since 2016. (Ibid., p. 13, 14.)

While this category is not exclusive to potential product-related fatalities, such fatalities certainly conjure up such considerations. Certainly, California workers experience many more non-fatal workplace injuries (120,000 for private industry; state and local government about 33,000). If the 12% statistic holds true for non-fatal injuries, then over 18,000 workers a year (50 a day) are injured just by objects or equipment alone. Therefore, it is important to be able to identify, investigate, and analyze a potential product liability case in a workplace setting.

Unlike some non-industrial (e.g., car accident) injuries, it may be difficult to identify the product as it is typically not in the client’s control and sometimes not even under the employer’s control. After identifying that a product is responsible for an injury, one must inquire into whether a defect in the product caused the injury. If there is a potential defect, analyze the worker’s and employer’s role for any contribution to fault. What follows is not an examination into product liability law but helpful tips on investigating a defective product in a third-party case, with illustrative case examples.

Obtaining a complete description and detailed sequencing of the mechanics of the injury should be the first order of business. This is intuitive, but this is likely going to be more involved than a run-of-the-mill slip and fall or car accident. This will lead to information about the product, as well as causation (discussed below).

It is important at this point to remain open-minded. The chief goal is to identify the product. Satisfying the elements of a product liability cause of action and other considerations can take a back seat for the time being. The client-worker may have very minimal information about the product model, manufacturer, etc., but they are your obvious first resource and can still provide useful data. Spending a decent amount of time with the client reviewing the injury and his workplace can also go a long way in developing a trusting relationship with the client. Be sure to speak with any witnesses and coworkers, too.

Other than the client, there are several other resources available to assist in identifying the product.

1) Employers have a legal obligation to report all workplace injuries to Cal/OSHA and “immediately” report those concerning serious injury or death. (Lab. Code, § 6409.1.) Cal/OSHA can investigate any workplace injury but must investigate those resulting in serious injury or death. (Lab. Code, § 6313.) Therefore, Cal/OSHA can be an excellent resource to find out more about the product in question. Cal/OSHA records can be requested on their website, and depending on the case, see if the investigator is willing to meet with you about their findings. This person could prove to be a valuable resource and may have even seen the product at issue.

2) Obtain the employer’s entire file for the worker. While the worker has a right to their “personnel file” (Lab. Code, § 1198.5), it may be best to issue a subpoena through the Workers’ Compensation case because a subpoena also permits requests into incident-related documents that may not be in the employee’s personnel file. Three, along these lines, request the Workers’ Compensation insurance carrier’s (and/or the claims administrator) entire file for the worker’s injury. Along with medical records, the carrier may have performed its own inspection and fault analysis into the product in question. This happened in one of the case examples below (drill case). These sources are not only helpful to identify the product but will be helpful later in the case.

3) Turn to the obvious sources of identification such as photos, videos, the internet, etc. It is tempting to simply glance at incident photographs or a video but identifying the product can require a keen and patient eye. A model number, brand name, or other identifying mark may be small, fleeting, and easy to overlook. The internet will probably not be useful until the product identity is narrowed a decent amount. Thus, it should likely only be used as a refining tool. Notably, these investigative tools are provided in no particular order but are case dependent.

As an aside, it may take the case to proceed to litigation and discovery before the product and/or its manufacturer can be identified. Therefore, it is critical to properly plead the DOE defendants into the product liability cause(s) of action of the complaint.

So you have identified the product, what now? The beauty of the third-party case is that it can be used to obtain valuable discovery about the product. Getting eyes and hands on the product is invaluable; setting an inspection of the product through the Workers’ Compensation case provides this opportunity. Prior to any inspection it is worth hiring an expert as they will play a critical role in the inspection and will hopefully have some valuable insights into the product.

While there is no labor code statute to request the specific product be produced for inspection (i.e., Code of Civ. Proc., § 2031.010 et seq.), Hardesty v. McCord & Holdren, Inc., 41 Cal. Comp. Cases 111, 114-115 (Cal. Workers’ Comp. App. Bd. March 16, 1976) affirms the civil policy for liberal discovery in Workers’ Compensation cases and holds that the Workers’ Compensation judge has the authority to issue discovery orders that are outside the discovery allowed in the Labor Code. Further, Labor Code section 5701 allows for an “inspection of the premises where the injury occurred,” which can help in a situation like the conveyor belt case example below. The goal is to use the Workers’ Compensation case to get hands on the product as soon as possible.

The product involved in the injury has been identified, so turn to the next step of determining liability. At this point, a brief overview of product liability law is instructive. “In a product liability action, every supplier in the stream of commerce or chain of distribution, from manufacturer to retailer, is potentially liable”. (Edwards v. A.L. Lease & Co. (1996) 46 Cal.App.4th 1029, 1033.) A product can be defective in its design, warning, and manufacture. (Webb v. Special Electric Co., Inc. (2016) 63 Cal. 4th 167, 180 [202 Cal. Rptr. 3d 460].) In all practicality, a vast majority of product liability cases are of the design and warning defect kind rather than manufacturing.

A defective design can be proven through either of two tests. One, the consumer expectation test is “whether the product performed as safely as an ordinary consumer would expect when used in an intended and reasonably foreseeable manner.” (Johnson v. United States Steel Corp. (2015) 240 Cal.App.4th 22, 32 [192 Cal.Rptr.3d 158].) Two, a product is defectively designed if it is established that, “on balance, the benefits of the challenged design outweigh the risk of danger inherent in such design.” (Barker v. Lull Engineering Co. (1978) 20 Cal.3d 413, 432 [143 Cal.Rptr. 225].) “Under ‘warning defect’ strict liability, a product, even though faultlessly made, is defective if it is unreasonably dangerous to place . . . in the hands of a user without a suitable warning and the product is supplied and no warning is given.” (Wright v. Stang Manufacturing Co. (1997) 54 Cal.App.4th 1218, 1230 [quotations and citations omitted].) A manufacturing defect is one in which the product “differs from the manufacturer’s intended result or from other ostensibly identical units of the same product line.” (Barker v. Lull Engineering Co., supra, 20 Cal.3d at p. 429.) Overarching it all is that a defect must have caused the worker’s injury. (Soule v. General Motors Corp. (1994) 8 Cal.4th 548, 560 [34 Cal.Rptr.2d 607].)

Of course, there is a plethora of case law concerning product liability that is beyond the scope of this article; however, these basic tests must be in mind when analyzing whether a defect caused the worker’s injury. Using the information obtained from the investigation and (hopefully) inspection of the product, see what hole the peg fits in. Did the product blatantly fail to meet a consumer’s expectation of safety? Was there a warning? Is there a cost-effective alternative design that would have prevented the injury? Was the product different from others off the assembly line? As with above, consulting with an expert can greatly assist in this analysis.

Once your peg has found its hole, consideration must be given to the worker’s and the employer’s actions in relation to the product. Regarding the worker, this analysis goes a little beyond a traditional comparative fault analysis. Certainly, one must inquire into whether the worker did something wrong or did something to contribute to the injury. The worker may have been (and likely was) operating the product when the injury occurred. Therefore, one must inquire into the reasonable and foreseeable use of the product. (See Perez v. VAS S.p.A. (2010) 188 Cal.App.4th 658, 684-685 [115 Cal.Rptr.3d 590] [liability may still exist for foreseeable misuse of the product].) Use the Workers’ Compensation case (e.g., subpoenas, depositions, etc.) to investigate and obtain this kind of information.

Regarding the employer, similar inquiries need to be made about its role with the product. For example, did the employer modify or otherwise alter the design of the product? This may remove the original manufacturer/designer of the product from liability. Did the employer encourage and/or ignore unsafe use of the product at the expense of productivity? Did the employer properly train its workers on the product? These are not just comparative fault considerations but also go to employer negligence that can reduce or eliminate the requirement for the worker to pay back benefits paid in their Workers’ Compensation case. (Witt v. Jackson (1961) 57 Cal.2d 57, 73 [17 Cal.Rptr. 369].)

Three relatively recent cases handled by our office help illustrate some of the issues raised in a third-party product liability case.

Our client was injured at a newly built distribution center with a series of conveyor belts.

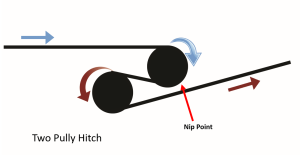

The conveyor in question was long and operated with a “two-pulley hitch.” The client went to grab a loose water bottle at the nip point, and his hand was essentially sucked into the two-pulley hitch. The resulting injury was a catastrophic arm break.

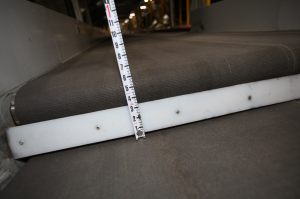

Our office was able to get an inspection of the distribution center and conveyor in the Workers’ Compensation case. (See Lab. Code, § 5701 [“inspection of the premises where the injury occurred”].) This provided essential information about the two-pulley hitch, the operation speed of the conveyor, where safety devices and warnings were located, and allowed the expert to develop their opinions.

The inspection also revealed that a plastic guard was placed (post-injury) at the nip point, which were required to have safeguards. Significantly, the subsequent remedial remedy defense is inapplicable in products liability cases. (Ault v. International Harvester Co. (1974) 13 Cal.3d 113, 118 [117 Cal.Rptr. 812].) The plastic guard was helpful because it was germane to the defect analysis – it prevented body parts from going past the nip point and getting tangled in the two-pulley hitch.

Our client was injured when a mobile coffee cart – being used for the first time – fell on (and fractured) his leg. This case posed some significant issues as the employer had no control over the cart, there was no OSHA report, and the client did not have a very good description of what happened or of the cart. All we really had was a single photo of the incident (pictured). Additionally, the cart was the first (and only) of its kind, which posed difficulties in finding any kind of specifications for it. Given the lack of information, we set the inspection (with our expert) of the cart as soon as possible. Discovery also resulted in documents and communications from shortly after the client’s injury concerning potential safety upgrades to the cart. The fact that this was the first and only time the cart was used boded well for our defect analysis.

Our client was on a mobile drill rig, drilling a hole in the ground when the hydraulic support beam came loose and crashed down on him. It fell because the nut securing the beam came loose during operation.

A guaranteed measure to prevent this (the nut walking off the bolt because of significant vibration) from happening is to put a cotter pin through the bolt; matching this with a castle nut provides even more enhanced safety. Indeed, this is exactly what the manufacturer did. Shortly after the incident, the company put out a memo stating that the cotter pin and castle nut should be employed in all of its machines, which happened on the subject product (pictured below).

As with the conveyor, the subsequent remedy provided relevant information about the defect. The Workers’ Compensation insurance carrier also conducted their own fault analysis and even retained control over the failed components.

This likely occurred because the employer was the owner of the product. The manufacturer was (and is) well known, so there was a good amount of information about the product available online. While no case is “easy,” the information obtained in the Workers’ Compensation case greatly assisted this case once in litigation

California workers are being injured and killed by products on a daily basis. Conducting a thorough investigation into the product and then into fault must proceed accordingly. Using the discovery and investigation tools available in a Workers’ Compensation case provides valuable assistance in these efforts and will help the case once in litigation. Each product liability case provides a unique situation, and just like a box of chocolates, you never know what you are going to get. That’s where our Orange County workers’ compensation attorneys can help.

By: John A. Montevideo and Michael K. Teiman